An abolitionist pastor of Swiss origin: Benjamin-Sigismond Frossard (1754-1830) (EN, FR)

- anneauxdelamemoire

- 28 mars 2023

- 5 min de lecture

An abolitionist pastor of Swiss origin: Benjamin-Sigismond Frossard (1754-1830)

Born in Nyon, in the Swiss canton of Vaud, Benjamin-Sigismond Frossard completed his primary schooling in Lausanne, before continuing his studies at the Geneva Academy. Upon graduation, he was ordained a pastor in 1777. He then moved to Lyon to carry out his religious duties. It wasn’t long before he became involved in the abolitionist struggle and became a member of the French Society of Friends of Black People, and at the end of his life, of the Society of Christian Morals.

Commitment to the abolitionist cause

In Lyon, in addition to his ministry, Frossard had a rather active social life and was a member of several learned societies. Amongst his acquaintances, there was the philanthropic banker Benjamin Delessert, the young Jean-Baptiste Say, and journalist Jean-François Blot who introduced Frossard to Brissot in 1782. The latter was a journalist and political activist, as well as the leader of the liberal Republicans.

From December 1784 to early June 1785, he travelled to England, a journey that would prove to be decisive in his future commitment to the anti-slavery cause. There he met early abolitionists, like Thomas Clarkson and Granville Sharp. He visited ships used in the trading of enslaved peoples. He also met with Pastor Hugh Blair, whose he had translated in 1784.

Upon his return to France, he prepared his great work , published in Lyon in 1789. The title was reminiscent of the work (1771) by the Quaker Anthony Benezet, a resident of Philadelphia, and initiator of the modern abolitionist movement.

The book is divided into two volumes. The first describes the reality of trafficking and the trade of enslaved African peoples; the second discusses their foundations and calls for their end. A fervent admirer of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the latter’s philosophy pervades Frossard’s book: the “Black Man” is naturally good, rather, it is the civil institution of slavery that corrupts his “nature”, but he is susceptible to moral progress by means of religion. The basis of his argument is monogenism: “ teaches us that having a common origin, there is no difference in their primitive constitution.”

Like Benezet, he included a plea for a new colonization of Africa, which would replace the trafficking and deportation of human beings with the establishment of free settlements, based on voluntary labour. Frossard first sought to convince the owners of enslaved African peoples that their interest, as well as their safety, lay in the gradual abolition of slavery. Moreover, he was in favour of a form of compensation for the masters to offset their losses.

Membership of the Society of Friends of Black People

With his work serving as a recommendation, Frossard became a member of the Society of Friends of Black People, which at the time, was particularly prominent. On 12 December 1792, he presented to the Convention his , which included the main arguments in his book.

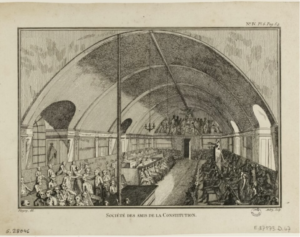

Around this time, Benjamin-Sigismond Frossard began a political career in Lyon. On 12 December 1789, he founded the Society of Friends of the Constitution and was elected administrator of the Lyon district. He devoted himself to the construction and establishment of the Institut de Lyon, a public educational institution offering post-secondary studies, where he himself taught as a professor of morality and natural law. Frossard and his friends, all liberal reformers, spoke out against radical Jacobins. The situation degenerated and the city veered towards civil war. On 2 May 1793, Frossard resigned from his administrative position, and deemed it more prudent to seek refuge in Clermont-Ferrand, where he stayed with his family until February 1795.

He then left for Paris, where he resided from February 1795 to February 1809. With Lanthenas, he became involved in projects that aimed to revive the activities of the Society of Friends of Black People, which came to fruition in November 1797. He was one of the most visible figures of the abolitionist movement, which did not resist, however, its internal divisions and Bonaparte’s hostility.

From the Consulate and the Napoleonic Empire to the return of the French Kings (Bourbons)

In addition, Frossard regularly frequented the Parisian Protestant milieu and was thus associated with its religious organization under the aegis of the State between 1802 and 1808. In 1808, three faculties of reformed theology were created: Strasbourg, Geneva, and Montauban. The leaders of the faculty of Montauban entrusted Frossard with its organization. He left Paris for Montauban in April 1809 where he occupied the functions of dean of the institution and professor of natural law.

In April 1814, he welcomed the return of the Bourbons: the fact that Louis XVIII had guaranteed freedom of thought, conscience, and religion in the Charter was the main reason for this. During the Hundred Days, he signed the Additional Act to the Constitutions of the Empire, which led to his replacement at the head of the faculty in early 1816, and subsequently his removal from the office of pastor. Frossard attributed his dismissal to his activism for the cause of the African peoples: “a former and ardent advocate of the cause of the unfortunate Africans, I applauded the decree which abolished the trade of enslaved peoples.”

In 1821, he translated English abolitionist William Wilberforce’s book: . That same year, he joined the Society of Christian Morals, which comprised an internal committee against trafficking and the trade of enslaved African peoples, which revived the original abolitionist movement.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

About the authors

Bernard Gainot is Honorary Lecturer in Modern History, at the Université PARIS I Panthéon-Sorbonne and Associate Researcher at the Institute of Modern and Contemporary History (IHMC) ENS/Paris1. His areas of research include: the history of colonial societies in the modern period; imperial history, more particularly the conflicts in colonial spaces between 1763 and 1830; and the political history of Mediterranean Europe (France, Italy, Spain) between 1792 and 1830.

Bibliography

Robert Blanc. . Paris: Honoré Champion, coll. “Vie des Huguenots,” 2000, 373 pps.

Benjamin-Sigismond Frossard. Paris, 1793, in EDHIS (Éditions d’histoire sociale): 10, rue Vivienne, Paris, vol. VII, text 11, 32 pps.

Anthony Benezet. . Pinnacle Press, 2017 <1771>, 126 pps.; text presented by Marie-Jeanne Rossignol and Bertrand Van Ruymbeke. Paris: Publications de la SFEDS (French Society for the Study of the Eighteenth Century, 2017, 158 pps.

SEE MORE